Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (63 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

11.82Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

A functioning and non-delusional Wilson might have made his deal with Lodge, as there were only 13 Irreconcilables. Mrs. Wilson largely controlled the government now, and allowed her husband only a few minutes a day of normal exposure to business, so fragile was his condition. By not publicly admitting the extent of Wilson’s incapacitation, she denied him the public sympathy he would have received, and also denied the government the adequately effective leadership able-bodied and clear-headed cabinet members could have given. None of them remotely approached Wilson’s stature or intellect, but they were passably competent and decent men who would have done the necessary. If Vice President Marshall had declared Wilson incapacitated, he could have taken over the management of the government and he and Lansing, bandying about the name of the stricken president, could probably have got Lodge to help adopt most of what Wilson was seeking. Lodge objected especially to Article X of the League Covenant, which committed the League to resist aggression and was construed by Lodge as meaning that American forces could be committed to combat without a vote of the U.S. Congress. This was nonsense in fact and was largely just illustrative of the personal antipathy between Lodge and Wilson, and of Lodge’s desire to find an issue for the Republicans to win with in the 1920 elections.

In February 1920, the Senate, given the importance of the issue, agreed to reconsider the treaty, but positions had not changed, and Wilson, who was almost eager to die fighting for his treaty, would brook no compromise. He had just enough authority left to prevent all of the Senate Democrats from deserting to the Lodge compromise, and for good measure fired Lansing, for having convened the cabinet without notice to Wilson, though no business was transacted in the president’s name. Bainbridge Colby, who had served Wilson as a legal adviser at the Paris negotiations, was appointed to replace Lansing as secretary of state.

8. THE 1920 ELECTIONWilson asked the Democrats to make the 1920 election “a solemn referendum” on the League of Nations, and when they convened at San Francisco in late June they did endorse the League and the treaty, but professed a willingness to consider “reservations making clearer or more specific the obligations of the United States.” The Republicans had met earlier in June in Chicago, and as they were split between the western Progressive isolationists and Irreconcilables, and the Taft, Root, Hughes wing of enlightened juridically minded easterners, the Republicans waffled and opposed the League but not “an agreement among the nations to preserve the peace of the world.” The Republican convention was deadlocked for some ballots and then the party bosses, meeting in the original “smoke-filled room” in the Blackstone Hotel, settled upon the innocuous, genial, and probably suggestible or even malleable Senator Warren Gamaliel Harding of Ohio for president, and the taciturn governor of Massachusetts, Calvin Coolidge, who had gained popularity in the midst of the Red and anarchist scare by breaking a police strike in Boston, for vice president.

The Democrats, after 44 ballots, chose the governor of Ohio, James M. Cox, and the dynamic and evocatively named Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt for vice president. The Socialists nominated Debs again, despite the fact that he was serving a 10-year prison term for sedition because of his lack of enthusiasm for the war effort. The Prohibitionists nominated a candidate again, although, in one of the most insane policy initiatives in its history, the United States in 1919 had already ratified the Eighteenth Amendment to the Constitution prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages, thus reducing most of the entire adult population to the status of lawbreakers and handing over one of America’s greatest industries to organized crime, some of whose leading figures now became more prominent folkloric figures than its politicians.

The country was already settling into an era of unbridled absurdity and this election was not a solemn referendum on anything. The mood was one of frivolity, punctuated by reflexive fear. Because of Bolshevik propaganda and a modest spike in labor militancy, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer organized a full-scale Red Scare and on January 2, 1920, had 2,700 suspected communist agitators arrested in dragnets around the country. The Republicans promised “a return to normalcy.” The country didn’t want to hear any more of Woodrow Wilson’s Old Testament call to greatness nor any talk of a Covenant with anything, except a speakeasy and the stock market. Harding ran a front-porch campaign and just rode the trend. Wilson, so recently the conquering hero, was thought a quavering, peevish, churlish old man, hiding in the White House. There was a recession in the country, and considerable doubt about what the purpose of entering the war had been.

Harding won, 16.15 million to 9.15 million for Cox and 920,000 for Debs. (The Prohibitionists won 189,000 votes, even though Prohibition was already in effect.) The electoral vote was 404 to 127. The Republicans had almost 62 percent of the vote to 34 percent for Cox to just over 4 percent for the others. Given the Democratic hold on the South, it was a remarkable victory for a mindless, no-name Republican good-time-Charlie campaign, and a heavy rejection of Wilson. The great expansion of the franchise was due to the granting of the right to vote to women. Harding chose Charles Evans Hughes as secretary of state, and he and Andrew Mellon at Treasury and the international engineer and aid administrator Herbert C. Hoover at the Commerce Department would be the stars of the administration. Once in office, the Republicans showed no disposition at all to internationalism, and Harding lost little time in burying League participation once and for all.

This astonishing cameo appearance by America on the world stage had suddenly arisen in the brilliant mind of Woodrow Wilson, as the predestined role of America to lead the nations of the world to durable peace. And it had swiftly vanished in the fickleness of the American public and the academic unsuitability of Wilson to the vagaries of the checks-and-balances political system. He has been much disparaged for excessive idealism and for tactical mismanagement of his ambitions, and he has also been criticized for insufficient reverence for the Constitution of the United States. But he grasped that the United States could never embark on foreign enterprises without some idealistic as well as practical basis to them, and that the world could not be safe for democracy without the United States in the front lines of those defending it. As for the Constitution, he can’t be claimed to have foreseen the problems of gridlock in Washington or the prevalence of interests throughout the Congress, but he certainly had premonitions of these problems.

His presidency ended pitifully, with him shrunken and delusional. But he remains a haunting and compelling figure, courageous, eloquent, without opportunism, and stricken with misfortune, as well as flawed by impolitic hubris. He was a prophet; he was the first person to inspire the masses of the world with the vision of enduring peace, and though several of his most distinguished predecessors had vaguely referred to America’s vocation to lead and the world’s eventual dependence on it, it fell to him to try to effect that immense change in America and the world. He was a very able war leader and a decisive influence in preventing German victory. That he did not win the peace does not deny him the great homage he deserves for seeing so clearly the need for American intervention and for a new structure of international relations. America was briefly struck by infelicity. Without the breakdown of his health, Wilson might have got America into the world; and a healthy Theodore Roosevelt would have led America into the twenties to a very different and more observant drummer than Warren Harding.

For the world, this sudden appearance and withdrawal of America opened a long era of blaming the United States for every conceivable ill in the world. America was perceived and represented as a great cuckoo bird that might fly out of its hemisphere at any time making loud and portentous noises and then abruptly return, slamming the door behind it. It conformed to European desires to imagine that, despite its undoubted power, it was a silly, vulgar, and irresponsible place. The Wilson interlude on the world stage had been brief and had ended badly, but without it, the Allies would not have won the war, and the United States would not so surely and capably have come to the rescue of the Old World when it blundered, by its own errors, into war again, after, as Foch predicted, “a twenty-year armistice.” Wilson failed, but he was the co-victor of World War I and, in a way, of World War II, and no one else, except possibly Winston Churchill, can make such a claim.

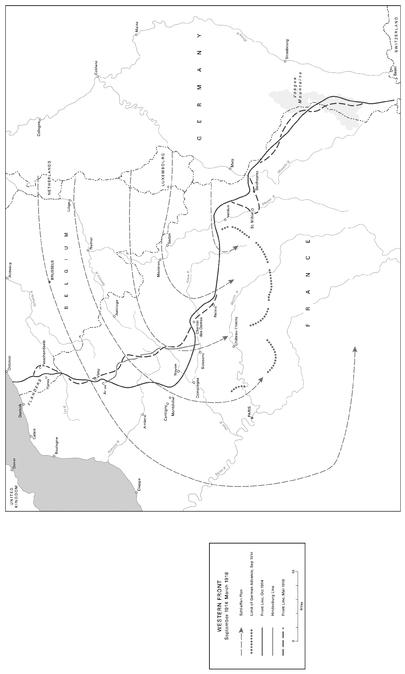

Western Front in WWI. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

Wilson permanently altered American foreign policy from the bantam rooster, Yankee Doodle rodomontade it had been under Jackson and in Daniel Webster’s letter to Hülsemann in 1850 (Chapter 7), and the hemispheric prowling and growling that had gone on from the expulsion of the French from Mexico in 1867 to Wilson’s own ludicrous punitive mission in Mexico nearly 50 years later. Its appearance among the Great Powers, though fleeting, showed the more astute observers, such as British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey, that America was “a gigantic boiler. Once the fire is lighted under it, there is no limit to the power it can generate.” The Republicans through the twenties pretended that they could substitute the sonorous espousal of peace and disarmament in place of contributing usefully to the correlation of democratic, stabilizing forces. Nothing would happen in the twenties while Germany and Russia were pulling themselves together, but if democracy failed in Germany and a nationalist government resulted, Communist Russia would hold the balance in Europe, an event that could cause almost all Europeans to become rather nostalgic for the Americans.

9. WARREN G. HARDING AND CALVIN COOLIDGEThe Harding administration made its first symbolic enactment of its anti-League substitute for pursuit of the peace process by responding to Irreconcilable senator Borah’s resolution requesting a conference to discuss naval disarmament. It invited all the major powers except the German and Russian pariahs to Washington for that purpose, and also to discuss Pacific and Far Eastern questions. The American delegation was headed by Hughes, Root, and Lodge. Hughes was elected conference chairman and proposed not only a limitation of naval construction but the scrapping of large numbers of warships. Since the German fleet had already destroyed itself and the Russians were not invited, it was an orgy of self-enfeeblement by the victorious Allied powers. The U.S. agreed to scrap 645,000 tons, Britain 583,000 tons, Japan 480,000 tons, and so forth, and ratios of capital ships (over 10,000 tons and guns of more than 10-inch diameters) were to be 5 U.K, 5 U.S., 3 Japan, and 1.67 each for France and Italy. There was to be a 10-year moratorium on new capital-ship construction. There were separate treaties governing use of submarines, banning asphyxiating gases at sea, recognizing reciprocally rights in the Pacific, abrogating the Anglo-Japanese Treaty, and pledging all against the aggression of any power; there was the usual claptrap about guaranteeing Chinese independence and territorial integrity and the Open Door, which was itself a mockery of Chinese sovereignty; restoration to China of some control over her customs and of Shantung and Kiachow from Japan; and there were some agreements governing trans-Pacific cables. U.S. Senate ratification was heavily conditionalized. (The Chinese attended and had a ragtag of assets in what they called their “water force.” They successfully rebutted the sarcasm of the upstart Japanese at the conference.)

The Pacific and Chinese provisions were ignored, as was Japan’s pledge to naval moderation. The net effect was simply to deprive the major Western powers of 1.3 million tons of warships, including more than 20 capital ships that could have been useful in future conflicts, such as in convoy protection and support for amphibious landings. Nor should the British have been in such a hurry to allow the United States parity with it in naval forces. The initial American reaction was prideful euphoria that it was contributing importantly to world peace without surrendering sovereignty to the League. Of course, this was a mirage.

The next great issue was war debts. The United States was owed $10,950,000,000 from the various European powers, and the British and the French early proposed that they cancel their debts in exchange for their cancellation of debts from others, including German reparations. Wilson and his successors refused. The American attitude was summed up in Coolidge’s rhetorical question: “They hired the money, didn’t they?” However, financial realities imposed themselves very inconveniently. The World War Foreign Debt Commission was set up in February 1922, and a 62-year payback with an interest rate of 2.135 percent was agreed. In 1924, Italy arranged the elimination of 80 percent of its debt and an interest rate reduction to 0.4 percent. In 1926, the French achieved a 60.3 percent reduction, and a rate of 1.6 percent.

Other books

The Shadow of the Torturer by Gene Wolfe

His Witch To Keep (Keepers of the Veil) by Zoe Forward

Devoted by Jennifer Mathieu

Prototype by Brian Hodge

Must Love Highlanders by Grace Burrowes, Patience Griffin

Sex, Murder, and the Meaning of Life by Douglas T. Kenrick

War-Dancer (Tales of the Commonwealth Book 4) by Noel-Morgan, Tom

Into the Rift by Cynthia Garner

Cold Quarry by Andy Straka