A Company of Heroes Book Three: The Princess (25 page)

Read A Company of Heroes Book Three: The Princess Online

Authors: Ron Miller

“So?”

“Well, no one could have predicted it, but there seems to be some sort of . . . well, critical mass, I suppose you could call it, beyond which the heat produced by the metal increases beyond all control.”

“You mean that the Kobolds have accidentally

melted

Strabane?”

“They do feel terrible about it.”

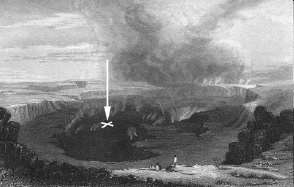

The arrow marks the original location of Strabane Castle

.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

FINAL WORDS

The four friends and their two prisoners leave the next day for Blavek, leaving behind a vast, circular basin filled with a scabby lake of heaving, heavily swirling lava; a cauldron into which is stirred a castle and a treasure as its most savory ingredients. Bronwyn does not suspect it, but the nascent volcano eventually proves to be instrumental in the recovery of Tamlaght’s economy. Although the loss of Payne’s loot should have been tragic, the final, irreversible, irresistible blow to the impoverished nation, since most of the money and treasure he had accumulated had belonged to the people and the state, or the Church which had gotten it from the people in the first place, the creation of the benign volcano ultimately more than made up for that. It eventually became one of the most popular tourist attractions in the northern hemisphere, once Tamlaght reluctantly abandoned its xenophobic isolationism, and within half a dozen years generated many times the amount of money that had been originally melted down, mixed and stirred into the amorphous magma. Several rustic hotels grew up nearby, as well as a small resort community. Blavek benefitted, too, by being the nearest seaport and large city. Its tawdry hotels were refurbished to suit the tastes of its Continental visitors and its restaurants vied for the trade of more sophisticated palates. Eventually, the natural geothermal area in the southeast is also opened to the public by enterprising entrepreneurs who established regular coach service between their resorts and the capital, providing unwelcome but useful competition with the Strabane caldera. The abbey of St. Woncible is rebuilt. There is talk of a bridge across the Strait.

This is all, however, anticipatory.

Ferenc had recovered soon after arriving at the hut, apparently none the worse for his concussion, though it is difficult to tell, all things considered. Payne, however, is in much worse condition. Not physically, he had suffered no serious wounds in his fight with the princess, and except for some loss of feeling in his extremities suffered no permanent injury in his capture. The sight of Strabane sinking into the ground like a foundering ship, however, has disconnected something in his already tenuously wired brain. He stares at the crumbling castle with bulging eyes and slack lips, an expression that remains more or less frozen. All the way back to Blavek he keeps his face turned toward the opposite direction, and so painful does this tortured posture look that even Bronwyn finally relents and allows her prisoner to be placed backwards on the horse. All the while he is muttering to himself in what sounds like a kind of droning chant. Bronwyn feels a kind of horror when after several days she realizes that he has been counting. “ . . . thirteen million three hundred and twelve thirteen million three hundred and thirteen thirteen million three hundred and fourteen . . . “ is the total that he had achieved when the princess finally overhears his words. He continues the monotonous ritual for the full two weeks of the journey.

There are only the two animals for the first several days and with the exception of Payne, who is never allowed to be untied, and Thud (out of kindness for the horses), turns are taken riding. Farms are eventually reached where extra animals are commandeered. At the first of these, Bronwyn, Thud, Rykkla and Gyven obtain their first substantial meal in weeks. Bronwyn allows the kindly wife of the farmer to tend her wounds, some of which have become inflamed and ugly-looking. Fortunately, none of the cuts had penetrated through the muscle, the most painful are those that had nicked her ribs. She gratefully abandons the remnants of her uniform (she had been wearing Gyven’s shirt since leaving the castle), accepting clothing from the family, who have a son more or less Bronwyn’s size. Outfitted in simple, clean homespun trousers tucked into her high boots, shirt and jacket, and broad-brimmed felt hat, a well fed, neatly bandaged Bronwyn feels fit and confident, anxious to complete this last leg of her inordinately and unexpectedly long journey.

Gyven rides at her side, tall and brown, his long black hair tied in a looping queue at his neck. His blousy shirt billows in tbe wind like a sail and his rough-hewn profile cuts the air like the prow of a ship. He looks like a dime-novel hero.

Payne Roelt rides behind him, tied to the back of Gyven’s saddle, still counting, always counting.

Rykkla has her own horse, following the princess’, and Thud strides behind them all, negligently carrying the king like a satchel, his easy stroll effortlessly keeping pace.

Gyven turns to the princess and asks in his leisurely, precise accent, “Are you happy now that it’s all over?”

She doesn’t answer for a moment, deciding how honestly she can or will reply. “I really don’t know. Maybe not. I don’t know. Nothing really seems to be over. It all seems so, so anticlimactic, somehow. I suppose I’ve accomplished everything I set out to do, but I just can’t make it seem as important as I thinks it would be. I just feel tired; I want to get it all over with and get on with things.”

“Like what? Are you going to assume the throne now?”

“I’ve been thinking about that. I guess I’d always taken it for granted that I would, if I thought about it at all. To be truthful, I never really thought very much beyond beating Payne and my brother. I haven’t decided what I’ll do now.”

“Someone has to take the throne.”

“You know, Gyven, I’ve been worrying about that. I know it’s my duty, and I know it’s expected of me, but can’t find it in me to

want

to. This’ll sound awful, I know, I don’t like myself for feeling this way, but I’ve realized that I just don’t care.”

“Perhaps you’re only tired.”

“Musrum knows that’s true, but I don’t think that’s all there is to it. I’ve thought back, and I think that I’ve been feeling this way for a long time.”

“If you don’t take the throne, what will you do?”

“I don’t know that either.”

* * * * *

The journey to Blavek takes longer than that to Strabane: the pace is more leisurely and Bronywn, for one, is finding her anxiousness to return to the city eroding in indirect proportion to their increasing proximity. She takes every opportunity to call for rest stops, as often as she spies a shady knoll or they cross some cool, shadow-colored stream bubbling and slipping over the rounded rocks and pebbles of its bed. None of her companions seem to be in any more of a hurry than she is, and the diversions are accepted with enthusiasm and abandoned with reluctance.

Finding a deep hole in a river downstream from an ancient, arched stone bridge they were crossing, they tie their horses by the roadside, in the shade of an enormous willow, and hike down to the water’s edge. There they shed their clothing and laze for an hour or two in the cool, swirling water. Bronwyn swims to the center of the circular basin and, holding her body vertically, motionless, allows herself to sink like a plumb bob. The water is as clear as glass and she is suspended, weightless, in a transparent sphere, itself surrounded by an impenetrable gloom, like a decorative paperweight. She feels like the center of a new universe, like the gravitational locus aound which might accrete a whole new world. The others hang like pendants from the quivering mirrored ceiling above her, their wan, green-tinted, headless bodies looking like planets obediently orbiting her; the shifting, reticulated light swirling dowly over their soft landscapes like weather patterns: storms, cyclones, squalls and gales.

Later, they dry themselves by lying on the flat sun-baked rocks under an incandescent sun and the no less incandescent combined glare of Payne Roelt and Ferenc Tedeschiiy, both of whom had been left securely bound (but at least kindly placed in the shade on the bank). Is the former titillated by the sight of the two beautiful women? One tall, cinnamon-haired, with skin the color of clover honey, the other also tall, but with carbon-black hair and skin the color of wildflower honey? Is he disturbed by the sight of the princess he loathed, seeing her looking far healthier than he have ever hoped to see her? Or did perhaps the still-red wounds on her sides, arms and face provide some measure of compensation? Or did that distant haze over Payne’s eyes, which remained focussed upon a point a little beyond the long, sinuous, shimmering women, belie that apparent appreciation of them? Would a closer observer realize that the ex-chamberlain has, in effect if not fact, gone quite blind . . . though it is a color blindness, for instead of blackness he sees only flame-red and gold?

Bronwyn lies back upon her rock and lets the sun wash over her like warm butter, like amber embedding a hapless insect, like mineral-laden waters replacing the cells of the future fossil with jasper and onyx. She falls asleep and dreams an odd and disturbing dream.

In that dream Baron Sluys Milnikov comes to her looking, she thinks, very different than he had ever looked before. It is the same baron, of course, and she cannot understand what is so strangely different about him until she realizes that it is not

he

who has changed.

They are in a vast and well-kept park of a rolling and determinedly rustic aspect. There is a glassy pond with perfectly placed lily pads, willows arching gothically and a pair of swans drifting with choreographic perfection. Nearby is a gazebo made of gnarly bark-covered branches and logs, and small benches also made of artistically looping bent wood. She is sitting on one of these now.

The baron is tall and distinguished and very handsome. His moustachios tilt upwards like a pair of sharp clock hands indicating ten minutes past ten (or perhaps ten minutes before two), like a pair of black scissors threatening to truncate the prominent and aristocratic nose that juts forward like the prow of a torpedo ram, as though he were scenting something he can’t quite place. His neat little imperial looks more like a comma than an exclamation point. His sleek hair is combed straight back from his forehead, leaving grey wings over his temples, and his grey-green eyes twinkle with a humorous and absentminded glimmering. He is in the blood-red full dress uniform of the House of Milnikov and carries a polished scarlet-plumed helmet in the crook of his left arm. He seems immeasurably attractive and it is

that

perception that makes him seem so different to her.

She sees herself reflected in the mirrored dome of the baron’s helmet, distorted like melting taffy. It is then that she realizes she is nude. The baron seems to take no notice and it seems perfectly right, and absolutely correct to Bronwyn, too.

The baron makes a deep and elaborately formal bow.

“My dearest princess,” he says, “may I have the honor of this dance?”

She has not noticed it before, but there appears to have been a string quartet in the gazebo all along. They are playing the

Broken Heart Waltz,

one she seldom hears though it is a favorite. She stands and took the baron’s proferred hand.

She had always felt herself something of a child in the baron’s presence before now, but now that she is in his arms, as they spin to the sad music that swirls around them, as though they are being stirred in a warm syrup, she sees that she is as tall as he. She looks into his face and sees something there that no child would ever have perceived.

As they dances she plucks at his uniform and it falls away like dissolving tissue paper; the colorful pieces fluttering around them like the flakes of snow in a water-filled paperweight, like the gaudy feathers of a molting parrot, like the last leaf-filled winds of autumn. Beneath the uniform he is as nude as she. His body is long and lean and smooth rather than muscular, and the hair on his chest is grizzled. Yet she realizes that while the baron might be old enough to be her father, his age is a relative thing; he is by no means an old man. Or is the dream baron really a younger man?

She presses herself against him, and while they circle slowly something like a swarm of fireflies swirls around the couple, what she thinks is the bright confetti of the baron’s uniform is not: it is a cloud of faeries. They arrange themselves in bright concentric rings, in shifting helices that twine and intertwine like colliding galaxies. Spikenard and his luminous wives dance down her arms like droplets of molten gemstones, liquid topaz, emerald, citrine, ruby, amethyst. The shifting, submarine light lends a translucency to the bodies of Bronwyn and the baron, so that they seem to shimmer from within like paper lanterns.

“I loved you, my dear princess,” says the baron.

“I know that; I love you, too,” she answers almost automatically, as she always has, not noticing the baron’s use of the past tense. She steps back from the baron, realizing with very little surprise, a dreamy acceptance, that she is now dressed in her full uniform, from riding boots to the stiff brocaded collar that props her stubborn chin erect. Her torso is encased in the bright, impermeable shell of a polished steel curaiss. She looks down at it and sees her warped reflection grimacing back at her.

“You don’t understand, my dear. I more than loved you: I was

in

love with you.”

“Oh, Baron, how could you? Why didn’t you ever tell me? How could I have known?”

“I had to love you in silence. You know that.”

“But you

did

tell me, didn’t you? You tried to tell me anyway,” she says, with a sudden, bitter inspiration, “a hundred times. And I never noticed. I took everything you said and did for me for granted. As I always have,” she added bitterly, “with everyone.”

“Seeing you happy was always enough,” the baron replies with a smile, and she knows that he really means what he says. But what

is

it he is saying? How

can

that have been enough? She herself would never have accepted such an immaterial token from anyone.

The cloud of faeries swirls over his body like electrical sparks, encasing him in their phosphorescent orbits like some artful St. Elmo’s fire; he becomes a paper doll consumed by the flying sparks, a doll gift-wrapped in loops of incandescent wire, a doll cut from magicians’ flash paper, an erupting effigy in a pyrotechnic celebration.

Love him

! whispers a piccolo voice in her ear.

“What?”